Understanding PETA's Shelter

PETA's Sheter: Its Origins

It's impossible to tell the story of PETA's specialized shelter without talking a little about Ingrid Newkirk. Most people know her as PETA's fearless and controversial founder and leader, but before she helped found PETA in 1980, and devoted her life to saving animals exploited for food, clothing, entertainment, and research, Ingrid Newkirk devoted her life to saving companion animals.

Ingrid Newkirk entered the animal sheltering world in the 1970's, which was a pivotal time for shelter animals in terms of their survival and treatment. In the early 1970's, the rate of shelter euthanasia was the highest it has ever been. The United States was euthanizing somewhere in the neighborhood of 20 million companion animals annually, out of a total population of about 80 million animals--or about one quarter of the entire companion animal population, every single year. To put this in perspective, currently, the U.S. euthanizes between 2 million and 3 million companion animals annually, out of a population of about 160 million animals, or less than 1.875% of the entire companion animal population. What set shelter euthanasia on its path to its dramatic decline? A concerted effort on the part of shelter specialists and veterinarians to create services which would educate the public on matters of animal welfare and routine spay and neuter.

In Michael Specter's fascinating yet somewhat obscure 2003 piece about Ingrid Newkirk, "The Extremist," Newkirk's introduction to the sad state of American animal sheltering is described this way:

Ingrid Newkirk entered the animal sheltering world in the 1970's, which was a pivotal time for shelter animals in terms of their survival and treatment. In the early 1970's, the rate of shelter euthanasia was the highest it has ever been. The United States was euthanizing somewhere in the neighborhood of 20 million companion animals annually, out of a total population of about 80 million animals--or about one quarter of the entire companion animal population, every single year. To put this in perspective, currently, the U.S. euthanizes between 2 million and 3 million companion animals annually, out of a population of about 160 million animals, or less than 1.875% of the entire companion animal population. What set shelter euthanasia on its path to its dramatic decline? A concerted effort on the part of shelter specialists and veterinarians to create services which would educate the public on matters of animal welfare and routine spay and neuter.

In Michael Specter's fascinating yet somewhat obscure 2003 piece about Ingrid Newkirk, "The Extremist," Newkirk's introduction to the sad state of American animal sheltering is described this way:

Newkirk worked and volunteered at several Washington D.C. area animal shelters during the early 1970's, before returning to England for training at the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals to learn more about companion animal welfare. Upon returning to the states, Newkirk took a position at Montgomery County, Maryland's Department of Environmental Protection, working as an anti-cruelty officer, where she was charged with inspecting the county's animal holding facilities--pounds, shelters, animal research labs--for compliance with the county's and state's animals welfare regulations. From there, Newkirk took a position at Montgomery County's most notorious animal pound, having had the terrible duty of inspecting it for the county and witnessing the profound depths of its despair first hand. She bravely set to work bringing the facility up to code and creating and implementing effective adoption policies. From there, she earned a position as Washington D.C.'s first female Poundmaster. The nation's Capital's first low-cost spay and neuter clinic was created during Newkirk's tenure, and she worked closely with the D.C. Metropolitan Police to get shelter dogs in their stellar canine training program. From there, she became the Director of Zoonotic Disease for the District of Columbia Commission on Public Health, a position typically reserved for persons with medical degrees. From there, she founded and became the president of the world's most effective animal rights organization.

In June of 1996, Ingrid Newkirk moved PETA's headquarters from Maryland to Norfolk, Virginia, and in 1998, created PETA's Community Animal Project program (CAP), a small division within the greater organization itself that would deal specifically with cases of cruelty and neglect, primarily within impoverished sections of the Hampton Roads area. Most of the animals PETA's CAP program handled at that time were either victims of abject cruelty and neglect who required humane euthanasia, or were owned animals whose guardians needed assistance spaying and neutering their animal companions. In 2001, PETA set up its first mobile spay and neuter clinic, increasing the number of animals they could spay and neuter from hundreds to thousands. In 2002, PETA set up several rooms at their headquarters where any adoptable animals of whom PETA took custody could be responsibly held while they awaited transfer to traditional animal shelters, or adoption, usually by a PETA staff-member. PETA wasn't focusing on the healthy, happy animals of Hampton Roads. Healthy, happy animals don't need saving. PETA focused on the animals in the most dire of circumstances, the animals for whom no one else was coming to save. Ingrid Newkirk, a woman who was exquisitely qualified to run a traditional animal shelter, and had, saw the need for and opened a shelter for the primary purpose of providing humane services to unadoptable animals instead.

PETA's Shelter Today: Adoption

While PETA's shelter still primarily focuses on providing humane services to sick, injured, and unadoptable animals, their facility continues to dedicate several enriched, home-like rooms to housing the relatively few adoptable animals PETA receives, while they await adoption, foster, or transfer to a traditional animal shelter.

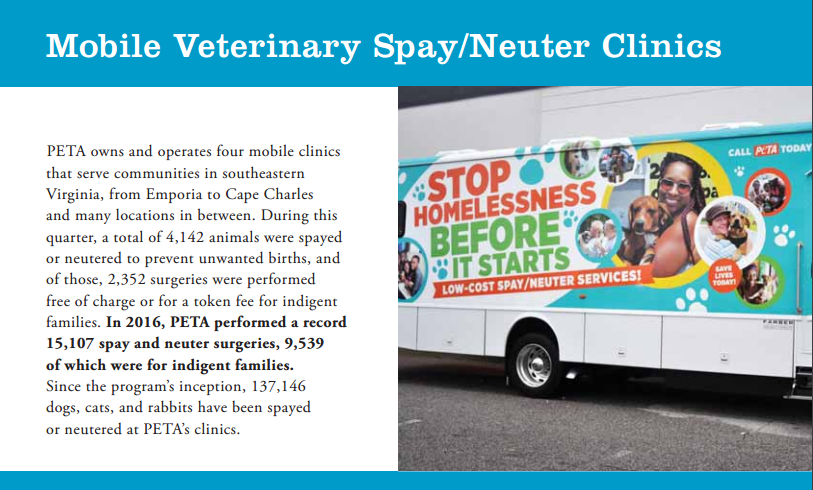

Spay and Neuter

In the mid 1970's when Ingrid Newkirk held the position of Poundmaster, and the nation's Capital's first low-cost spay and neuter clinic was created, companion animal euthanasia was at an all-time high. Nearly a quarter of the entire companion animal population was being euthanized annually. Shelter specialists like Ingrid Newkirk set shelter euthanasia on a path to steady and meaningful decline, by making affordable spay and neuter accessible.

Today, less than 2% of the entire companion animal population is euthanized annually, but there's still progress to be made. PETA's mobile spay and neuter fleet is in the community six days a week providing free and low-cost surgeries to communities that don't have access to traditional veterinary services, or simply can't afford them.

Today, less than 2% of the entire companion animal population is euthanized annually, but there's still progress to be made. PETA's mobile spay and neuter fleet is in the community six days a week providing free and low-cost surgeries to communities that don't have access to traditional veterinary services, or simply can't afford them.

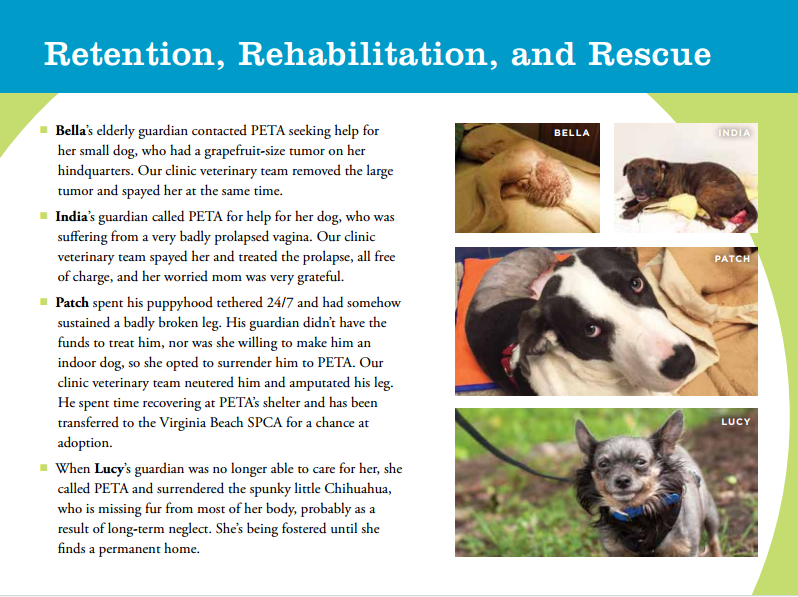

Retention, Rehabilitation, and Rescue

To learn more about how PETA saves community animals, click here.

Euthanasia

PETA's Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services animal reporting data and shelter inspection reports confirm that most of the animals PETA receives for euthanasia are received from their guardians because they either require humane euthanasia due to a current crisis of illness or injury, or are feral cats who are unwelcome and unserved by other shelters in their communities. There is absolutely no indication these guardians aren't acting in their animals' best interests by requesting this service from PETA's shelter, or that it's in any of their best interests not to be immediately euthanized.

Virginia Comprehensive Animal Law considers each of the three methods of shelter animal "disposition"--adoption, transfer, and euthanasia, to be equal under the law. Meaning, Virginia animal releasing agencies are not required to record and report any determinations they make about a companion animal's "adoptability."

The Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services does recognize that private animal shelters do receive owned community animals for the purpose of humane euthanasia, however. Dr. Kovich recently stated that with regards to shelters performing humane euthanasia as a community service to owned animals who are experiencing a current crisis of illness or injury, that it "does happens a lot," and that, "the proportions of euthanasia at shelters vary for different reasons and that is an important point to remember."

Allegations that PETA euthanizes adoptable animals are not evidence-based, because the State Veterinarian simply doesn't collect that data.

And because the state of Virginia only collects data on the animals that PETA takes custody of for the purposes of either adoption, transfer, and humane euthanasia, the overwhelming majority of animal served by PETA don't appear on their VDACS animal reporting summary records and are therefor unfairly absent in conversations about the work PETA does.

Animals find themselves at the receiving end of PETA's euthanasia services because of one of two circumstances has occurred; PETA's Community Animal Project (CAP) staff has come across a profoundly suffering community animal while performing community outreach duties, or someone within the community has contacted PETA's Norfolk headquarters to request assistance with an profoundly injured, ill, or unadoptable animal.

Only a fraction of the animals PETA's CAP program serves ever enter PETA's facility. The majority are served in their communities, in ways that are meaningful to them. PETA's CAP program isn't just about providing no-cost humane euthanasia to animals who require it. CAP program staff and volunteers provide other types of services to animals struggling in impoverished communities. They make food deliveries, transport animals to veterinarian offices for treatment and pay for their medical care, build and install all-weather animal housing, work with owners to get animals off of chains, and operate free and low-cost spay and neuter clinics throughout their service area.

Virginia Comprehensive Animal Law considers each of the three methods of shelter animal "disposition"--adoption, transfer, and euthanasia, to be equal under the law. Meaning, Virginia animal releasing agencies are not required to record and report any determinations they make about a companion animal's "adoptability."

The Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services does recognize that private animal shelters do receive owned community animals for the purpose of humane euthanasia, however. Dr. Kovich recently stated that with regards to shelters performing humane euthanasia as a community service to owned animals who are experiencing a current crisis of illness or injury, that it "does happens a lot," and that, "the proportions of euthanasia at shelters vary for different reasons and that is an important point to remember."

Allegations that PETA euthanizes adoptable animals are not evidence-based, because the State Veterinarian simply doesn't collect that data.

And because the state of Virginia only collects data on the animals that PETA takes custody of for the purposes of either adoption, transfer, and humane euthanasia, the overwhelming majority of animal served by PETA don't appear on their VDACS animal reporting summary records and are therefor unfairly absent in conversations about the work PETA does.

Animals find themselves at the receiving end of PETA's euthanasia services because of one of two circumstances has occurred; PETA's Community Animal Project (CAP) staff has come across a profoundly suffering community animal while performing community outreach duties, or someone within the community has contacted PETA's Norfolk headquarters to request assistance with an profoundly injured, ill, or unadoptable animal.

Only a fraction of the animals PETA's CAP program serves ever enter PETA's facility. The majority are served in their communities, in ways that are meaningful to them. PETA's CAP program isn't just about providing no-cost humane euthanasia to animals who require it. CAP program staff and volunteers provide other types of services to animals struggling in impoverished communities. They make food deliveries, transport animals to veterinarian offices for treatment and pay for their medical care, build and install all-weather animal housing, work with owners to get animals off of chains, and operate free and low-cost spay and neuter clinics throughout their service area.

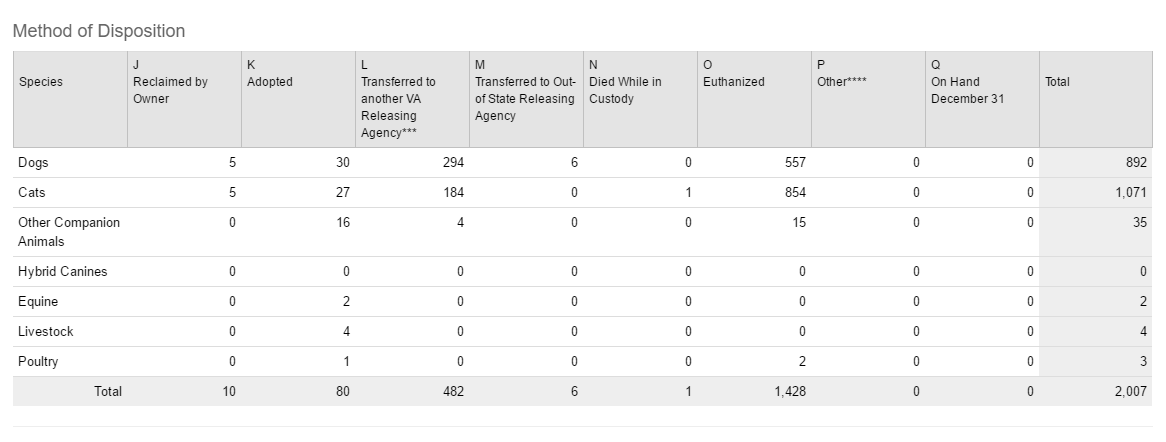

PETA's Shelter Statistics: VDACS

Virginia animal shelters are required by law to submit requested shelter data to the Virginia Department of Agriculture and Community Services' State Veterinarian annually. The VDACS publishes a summary of each facility's intake and disposition numbers on its website. Additionally, PETA publishes more detailed information on their website, in a quarterly format, in advance of the VDACS' annual summary reports.

This is what we know about the animals PETA handled through their shelter, based on information provided to and by VDCAS, and additional information PETA voluntarily reports on their website:

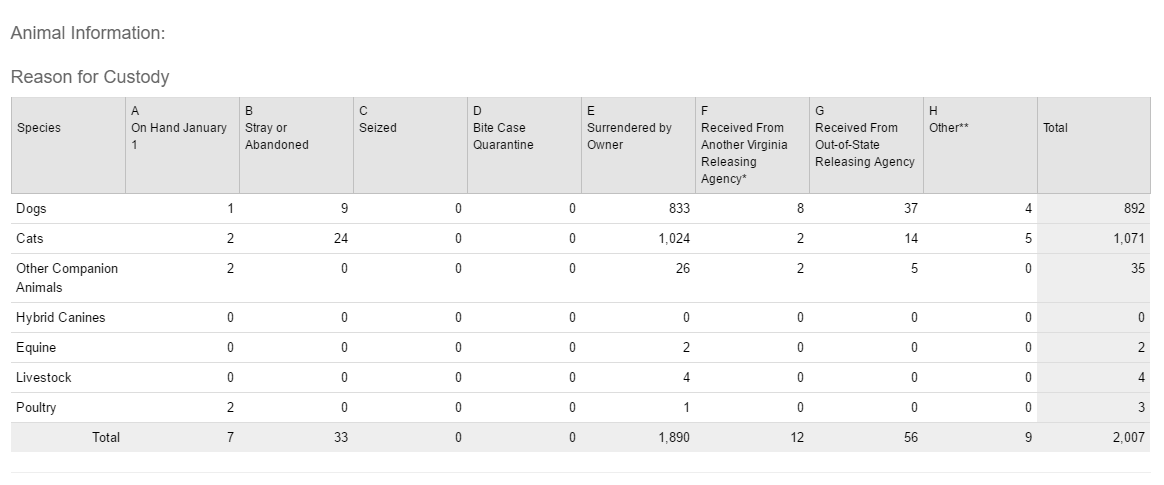

This is the "intake" section of PETA's VDACS animal reporting summary for 2016:

This is what we know about the animals PETA handled through their shelter, based on information provided to and by VDCAS, and additional information PETA voluntarily reports on their website:

- PETA took custody of 2,007 companion animals in 2016

- 1,890 of those animals were surrendered to PETA by a guardian or caretaker

- 1,428 of those animals were humanely euthanized

- 544 of the animals who were humanely euthanized were feral cats who were considered to be nuisances in their communities and who were not served by other shelters in their jurisdictions

- 440 of the animals who were humanely euthanized were euthanized for indigent guardians who couldn't afford traditional veterinary end of life care for their animals

- 482 animals were transferred to traditional animal shelters

- 80 animals were adopted through PETA's facility

This is the "intake" section of PETA's VDACS animal reporting summary for 2016:

Below is the "disposition" section of PETA's 2016 VDACS animal reporting summary:

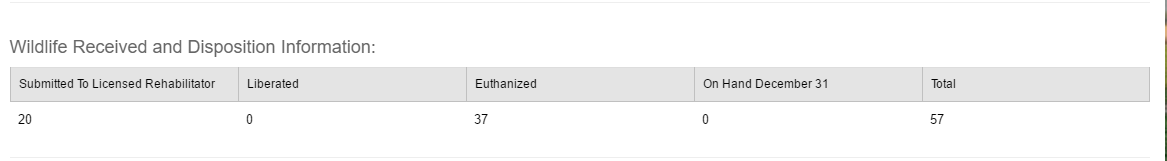

Below is the section pertaining to wildlife:

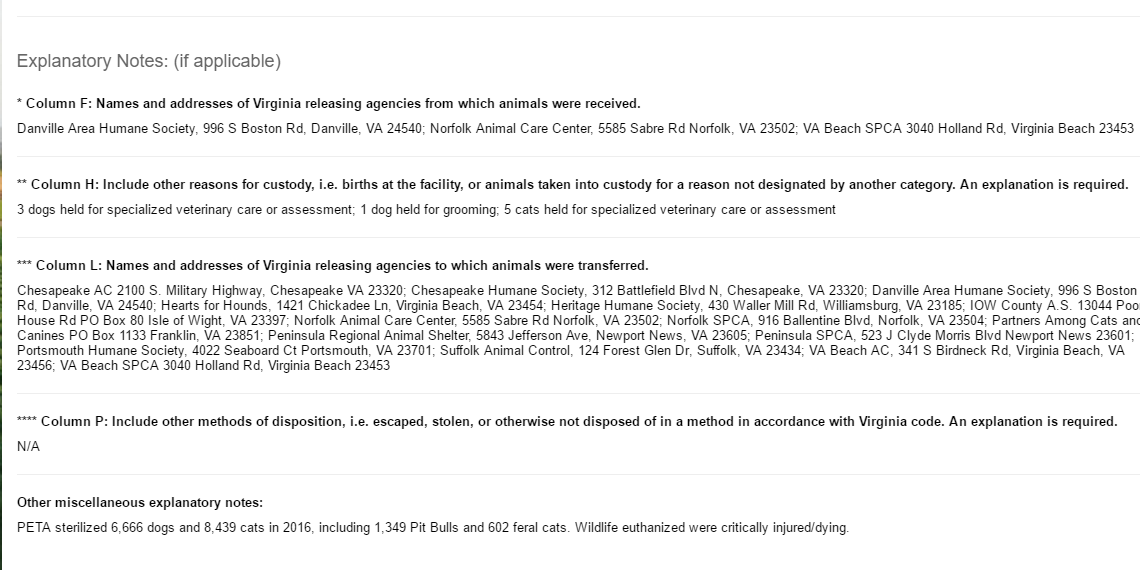

Below is a new animal reporting summary section the VDACS added for the 2016 reporting year, where additional information can be published. VDACS animal reporting summaries for previous years can be viewed here.

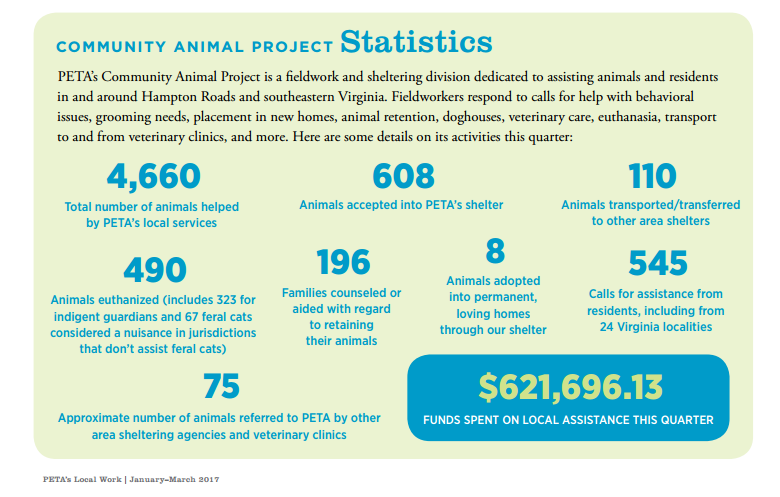

Additional Information about the Animals PETA Serves

PETA publishes additional information about the animals they serve on their website, on a quarterly basis: