SB 1381: In Like a Lion, Out Like a Lamb

|

On January 21, 2015, William M. Stanley, Jr., introduced a bill proposing a change to the definition of "private animal shelter," stating the legislation would clarify, "that the purpose of a private animal shelter is to find permanent adoptive homes and facilitate other lifesaving outcomes for animals."

On March 8, 2015, Senator William M. Stanley, Jr. wrote an opinion piece in the Virginian Pilot, "A Simple Bill to Save Pets' Lives," announcing that his family was adopting a shelter dog, an abandoned, elderly, and heart worm positive hunting hound whom, he wrote, would've been euthanized in a lot of Virginia shelters. Senator Stanley wrote, "This is the fundamental problem with organizations like PETA, which sees what it has but not what can be with just a little love, dedication and attention." Senator Stanley also wrote about his new legislation, stating it would take aim at PETA's controversial shelter practices. Citing a generally misunderstood "site visit report" pertaining to PETA's shelter, generated by the State Veterinarian back in 2010, Senator Stanley wrote that his new legislation, SB 1381, would fix a "strained interpretation of the law" that allows PETA's Norfolk facility to operate as an "animal shelter" and euthanize some 2,000 animals every year. |

|

"Each session of the Virginia General Assembly seems to hold a piece of surprise legislation, a bill that appears small, even innocuous, yet generates a tremendous amount of engagement by citizens, activists and lobbyists. This year, the surprise was my bill, SB1381, legislation that added one word, changed the tense of one word and changed the order of one phrase in an existing piece of Virginia code. It became a source of great debate and generated broad bipartisan cooperation in a legislative body often criticized for political polarization. SB1381 is a technical amendment in a section of the Virginia Code. It states that the primary purpose of a private animal shelter shall be to find permanent adoptive homes for those companion animals that the private shelter takes in."--Senator William M. Stanley, Jr.

But there's a rather interesting story behind the VDACS "site visit report" Senator Stanley referenced in the Pilot. In 2010, precipitated by an email to his office asking for clarification regarding the purpose of PETA's Norfolk animal facility, State Veterinarian, Dr. Dan Kovich, DVM, conducted a site visit at PETA's facility to get a better understanding of the type of work the animal rights group was doing there.

Though PETA's facility had been annually inspected by a State Veterinarian as an "animal shelter" for over a decade, Dr. Kovich felt it prudent at the time to reassess whether or not PETA's shelter currently met the statutory definition of "animal shelter" and whether it would continue to be inspected as such, or considered to be a "veterinary establishment" going forth.

As part of the reassessment process, Dr. Kovich spoke with Daphna Nachminovitch, the vice president of PETA's Cruelty Investigations Department and the person who oversees PETA's shelter. Additionally, Dr. Kovich performed an assessment of PETA's facility and analyzed the data contained in PETA's 2010 Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services "animal custody records." He then constructed charts and graphs that quantified the proportions of PETA's adoptions, transfers, and euthanasia procedures, in an endeavor to determine the facility's "primary purpose."

When Dr. Kovich generated this site visit report, he documented that according to Ms. Nachminovitch, the majority of animals that were taken into custody by PETA were considered by them to be unadoptable, and that Ms. Nachminovitch had indicated to him that adoptable animals were routinely referred to other area animal shelters for adoption. Consistent with Ms. Nachminovitch's statements, Dr. Kovich documented that according to the findings of his site visit, PETA did not operate a facility that primarily found homes for animals. Operating under the assertion that PETA's facility must operate for the primary purpose of finding permanent adoptive homes for animals, in order to meet the statutory definition of "animal shelter," Dr. Kovich documented that no further action would be taken regarding the findings of his site visit, until such time that Ms. Nachminovitch could respond with material supporting the "legitimacy of PETA for full consideration as an animal shelter."

Asserting the legitimacy of their facility for full consideration as an "animal shelter" was of paramount importance to PETA if they were to continue taking custody of animals for the purposes of adoption and transfer, and reuniting strays with their guardians. Interestingly, however, PETA's facility did not need full consideration as an animal shelter to provide the service of humane euthanasia to community animals who require it, since PETA already operated a "veterinary establishment" that employed at least one full-time veterinarian, and veterinary establishments can perform humane euthanasia as a veterinary service with no requirements that they report their euthanasia "numbers" to the state.

Ultimately, it was determined that PETA had had the law on their side the entire time. Dr. Kovich had made an honest mistake in asserting that facilities must operate for the primary purpose of finding permanent adoptive homes for companion animals, in order to be considered "animal shelters" by the state. At the time, this was the state of Virginia's statutory definition of "animal shelter":

"Animal Shelter" means a a facility, other than a private residential dwelling and its surrounding grounds, that is used to house or contain animals and is owned, operated, or maintained by a non-governmental entity including a humane society, animal welfare organization, or society for the prevention of cruelty to animals, or any other organization operating for the purpose of finding permanent adoptive homes for animals.

There had never been a requirement that PETA's shelter operate for the primary purpose of finding permanent adoptive homes for animals. Because PETA's shelter did operate for the purpose finding permanent adoptive homes for the relatively few adoptable animals they received, PETA's facility already met the statutory requirements for full consideration as an "animal shelter." On March 30, 2011, Dr. Kovich generated a superseding document stating that his office had completely reviewed the materials PETA submitted and that his office was satisfied that PETA's Norfolk facility met the statutory requirements for "animal shelter."

The 2010 "site visit report" was the artifact of a misunderstanding of the law. Virginia considers the following three methods of shelter animal disposition to be equal under the law; adoption, transfer, and euthanasia, with no preference given to any single method of disposition. There is no condition that shelters operate for a "primary purpose," even with regards to finding animals permanent adoptive homes. And despite what Senator Stanley wrote in his piece for the Virginian Pilot, none of the previous definitions of "animal shelter" and "private animal shelter" include the word "primary," and interestingly, neither does the legislation Stanley himself introduced.

William Stanley, Jr. and PETA probably don't see eye to eye on a lot of things. Senator Stanley made a point to say that his new adopted hound dog doesn't have to earn her keep as a hunting dog anymore, but the sad truth is that the Senator does support an industry that generates thousands of abandoned hunting dogs every year, just like the abandoned and heart worm positive dog he himself rescued. I was shocked to learn, and maybe you will be too, that Senator Stanley not only supports breeding and exploiting dogs for the hunting industry legislatively, he hosts annual fundraising events where dogs are provided to participants for the duration of his scheduled hunting event.

And while Senator Stanley may love rescuing dogs, species of wild "game" animals are served at the private reception following his annual fundraising bird kill. Senator Stanley misguidedly blames the euthanasia of abandoned hounds like his dog "Tanner" on the shelters that take them in, instead of the industry that leaves thousands of hunting dogs starved, neglected and abandoned every year. And rather than create legislation that protects hunting dogs like Tanner from the cruelty and abandonment that necessitates their admission into shelters, Senator Stanley is asking Virginia citizens to join him at taking aim at an organization that wants to end these dogs' exploitation. And he's asking them to overlook the fact that his proposed definition of "private animal shelter" didn't actually attribute a "primary purpose" with regards to private animal shelters.

"Each session of the Virginia General Assembly seems to hold a piece of surprise legislation, a bill that appears small, even innocuous, yet generates a tremendous amount of engagement by citizens, activists and lobbyists. This year, the surprise was my bill, SB1381, legislation that added one word, changed the tense of one word and changed the order of one phrase in an existing piece of Virginia code. It became a source of great debate and generated broad bipartisan cooperation in a legislative body often criticized for political polarization. SB1381 is a technical amendment in a section of the Virginia Code. It states that the primary purpose of a private animal shelter shall be to find permanent adoptive homes for those companion animals that the private shelter takes in."--Senator William M. Stanley, Jr.

But there's a rather interesting story behind the VDACS "site visit report" Senator Stanley referenced in the Pilot. In 2010, precipitated by an email to his office asking for clarification regarding the purpose of PETA's Norfolk animal facility, State Veterinarian, Dr. Dan Kovich, DVM, conducted a site visit at PETA's facility to get a better understanding of the type of work the animal rights group was doing there.

Though PETA's facility had been annually inspected by a State Veterinarian as an "animal shelter" for over a decade, Dr. Kovich felt it prudent at the time to reassess whether or not PETA's shelter currently met the statutory definition of "animal shelter" and whether it would continue to be inspected as such, or considered to be a "veterinary establishment" going forth.

As part of the reassessment process, Dr. Kovich spoke with Daphna Nachminovitch, the vice president of PETA's Cruelty Investigations Department and the person who oversees PETA's shelter. Additionally, Dr. Kovich performed an assessment of PETA's facility and analyzed the data contained in PETA's 2010 Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services "animal custody records." He then constructed charts and graphs that quantified the proportions of PETA's adoptions, transfers, and euthanasia procedures, in an endeavor to determine the facility's "primary purpose."

When Dr. Kovich generated this site visit report, he documented that according to Ms. Nachminovitch, the majority of animals that were taken into custody by PETA were considered by them to be unadoptable, and that Ms. Nachminovitch had indicated to him that adoptable animals were routinely referred to other area animal shelters for adoption. Consistent with Ms. Nachminovitch's statements, Dr. Kovich documented that according to the findings of his site visit, PETA did not operate a facility that primarily found homes for animals. Operating under the assertion that PETA's facility must operate for the primary purpose of finding permanent adoptive homes for animals, in order to meet the statutory definition of "animal shelter," Dr. Kovich documented that no further action would be taken regarding the findings of his site visit, until such time that Ms. Nachminovitch could respond with material supporting the "legitimacy of PETA for full consideration as an animal shelter."

Asserting the legitimacy of their facility for full consideration as an "animal shelter" was of paramount importance to PETA if they were to continue taking custody of animals for the purposes of adoption and transfer, and reuniting strays with their guardians. Interestingly, however, PETA's facility did not need full consideration as an animal shelter to provide the service of humane euthanasia to community animals who require it, since PETA already operated a "veterinary establishment" that employed at least one full-time veterinarian, and veterinary establishments can perform humane euthanasia as a veterinary service with no requirements that they report their euthanasia "numbers" to the state.

Ultimately, it was determined that PETA had had the law on their side the entire time. Dr. Kovich had made an honest mistake in asserting that facilities must operate for the primary purpose of finding permanent adoptive homes for companion animals, in order to be considered "animal shelters" by the state. At the time, this was the state of Virginia's statutory definition of "animal shelter":

"Animal Shelter" means a a facility, other than a private residential dwelling and its surrounding grounds, that is used to house or contain animals and is owned, operated, or maintained by a non-governmental entity including a humane society, animal welfare organization, or society for the prevention of cruelty to animals, or any other organization operating for the purpose of finding permanent adoptive homes for animals.

There had never been a requirement that PETA's shelter operate for the primary purpose of finding permanent adoptive homes for animals. Because PETA's shelter did operate for the purpose finding permanent adoptive homes for the relatively few adoptable animals they received, PETA's facility already met the statutory requirements for full consideration as an "animal shelter." On March 30, 2011, Dr. Kovich generated a superseding document stating that his office had completely reviewed the materials PETA submitted and that his office was satisfied that PETA's Norfolk facility met the statutory requirements for "animal shelter."

The 2010 "site visit report" was the artifact of a misunderstanding of the law. Virginia considers the following three methods of shelter animal disposition to be equal under the law; adoption, transfer, and euthanasia, with no preference given to any single method of disposition. There is no condition that shelters operate for a "primary purpose," even with regards to finding animals permanent adoptive homes. And despite what Senator Stanley wrote in his piece for the Virginian Pilot, none of the previous definitions of "animal shelter" and "private animal shelter" include the word "primary," and interestingly, neither does the legislation Stanley himself introduced.

William Stanley, Jr. and PETA probably don't see eye to eye on a lot of things. Senator Stanley made a point to say that his new adopted hound dog doesn't have to earn her keep as a hunting dog anymore, but the sad truth is that the Senator does support an industry that generates thousands of abandoned hunting dogs every year, just like the abandoned and heart worm positive dog he himself rescued. I was shocked to learn, and maybe you will be too, that Senator Stanley not only supports breeding and exploiting dogs for the hunting industry legislatively, he hosts annual fundraising events where dogs are provided to participants for the duration of his scheduled hunting event.

And while Senator Stanley may love rescuing dogs, species of wild "game" animals are served at the private reception following his annual fundraising bird kill. Senator Stanley misguidedly blames the euthanasia of abandoned hounds like his dog "Tanner" on the shelters that take them in, instead of the industry that leaves thousands of hunting dogs starved, neglected and abandoned every year. And rather than create legislation that protects hunting dogs like Tanner from the cruelty and abandonment that necessitates their admission into shelters, Senator Stanley is asking Virginia citizens to join him at taking aim at an organization that wants to end these dogs' exploitation. And he's asking them to overlook the fact that his proposed definition of "private animal shelter" didn't actually attribute a "primary purpose" with regards to private animal shelters.

The Transformation of SB 1381

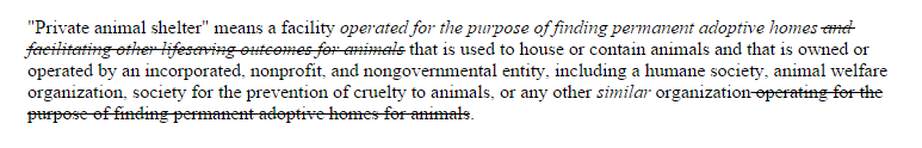

On February 23, 2015, based on recommendations issued by Agriculture, Chesapeake and Natural Resources, Robert Dickson "Bobby" Orrock, Sr., amended the proposed definition of "private animal shelter" to exclude the language, "and facilitating other lifesaving outcomes for animals," and the amended definition was signed into law on March 23, 2015, by Governor Terry McAuliffe, clarifying, "that the purpose of a private animal shelter is to find permanent adoptive homes for animals." Below is a representation of the definition as it existed prior to the introduction of SB 1381 (non-italicized text, with and without strike-throughs) , the changes SB 1381 proposed (italicized text, with and without strike-throughs) , and the legislation in its final form (all italicized and non-italicized text without strike-throughs):

By the time Senator Stanley's March 8, 2015 piece was published in the Virginian Pilot, SB 1381 had already been significantly amended, a fact that wasn't disclosed in the Virginian Pilot piece. Two weeks earlier, on February 23, 2015, based on sound recommendations issued by the Agriculture, Chesapeake and Natural Resources Committee, Delegate Robert Dickson "Bobby" Orrock, Sr., amended Stanley's proposed definition of "private animal shelter" to exclude the language, "and facilitating other lifesaving outcomes for animals." The House of Delegates passed the amended legislation that same day, and the bill was signed into law by Virginia's Governor on March 29, 2015.

Though SB 1381 never established that private animal shelters must operate for the "primary purpose" of finding animals permanent adoptive homes, PETA's detractors, including Heather Harper-Troje, claimed an unprecedented victory against the animal rights group, and all manner of misguided rumors about what change the legislation did and did not effect began to circulate.

The Draft Guidance Document: The VDACS Oversteps Its Authority

On March 26, 2015, three days after SB 1381 was signed into law, Arin Greenwood, the Animal Welfare Editor for the Huffington Post, and former research fellow and contributor for the notorious industry front group, Competitive Enterprise Institute, published the piece "Animal Advocates Cheer As Bill Aimed At High-Kill PETA Shelter Is Signed Into Law," featuring a VDACS' quote about the department's plans to create regulations that would "further clarify" the scope of Stanley's legislation:

"VDACS plans to develop a new regulation through the Administrative Process Act to further clarify the qualifications for a facility 'operated for the purpose of finding permanent adoptive homes for animals.' The agency expects that the three-step regulatory process required by the Code of Virginia will take two to three years to complete given the extensive stakeholder interest in this issue. The impact of the law on PETA or any other private animal shelter will not be known until the regulation is finalized."--VDACS' Statement to Huffington Post

Though Delegates that passed the amended legislation would later state that the bill never established that private animal shelters must operate for any primary purpose, and though the bill had never even contained the word "primary" or any of its synonyms, forces within Virginia and beyond redoubled their efforts to establish a "primary purpose" requirement with regards to private animal shelters, outside of the statute, by way of an accompanying "guidance document." On April 16, 2015, at their request, the VDACS met with what was described as "a number of proponents of SB 1381" to get their input; SB 1381 patron Senator William Stanley Jr., Debra Griggs of the Virginia Federation of Humane Societies, Robin Starr of the Richmond SPCA, and Will Gomaa of Maryland-based Alley Cat Allies met with VDACS Deputy Secretary of Agriculture Sam Towell, VDACS Commissioner Sandy Adams, and State Veterinarian Dr. Richard Wilkes, to express their concerns. The group of supporters was asked to submit their suggestions for a "guidance document" the VDACS would be drafting.

The VDACS rarely creates guidance documents. In fact, this guidance document was the first ever of its kind. But what made this particular document even more noteworthy was that the VDACS and several of the legislation's supporters were working together privately to draft it. Over the span of many weeks, the VDACS was creating regulations that would be put in place as soon as July 1, 2015, and they were doing it out of the view of most of the document's stakeholders. And what was maybe even more concerning was that the group seemed to be endeavoring to enact regulations contrary to the statute in its content. On April 28, 2015, barely a month after SB 1381 was signed into law, and two weeks after the VDACS had met privately with the group of SB 1381 supporters, VDACS officials were already going forth with the premise that the statute itself established that private animal shelters must operate for the primary purpose of providing permanent adoptive homes for animals, though Delegates who passed the bill would later say it didn't:

"SB 1381 changed the definition of a public animal shelter to require that a shelter have the finding of permanent, adoptive homes for companion animals as the primary mission of the facility. VDACS is developing criteria that will determine the primary mission of a public shelter and hopes to start using the definition for inspections near July 1. A facility must be designated as a shelter to be allowed to have trained and approved non-veterinarians perform euthanasia."--Dr. Wilkes, Virginia State Veterinarian in a Letter to the Virginia Veterinary Medical Association Dated April 28, 2015

It wasn't until May 6, 2015, and quite by accident, that word leaked out that SB 1381 supporters were meeting privately with VDACS officials to create the guidance document, and that regulation was on track to be implemented way ahead of the two to three year time frame the VDACS had committed to back in March. On May 7, 2015, PETA submitted a Freedom of Information Act request to the VDACS to obtain the materials pertaining to the drafting of the guidance document, at considerable expense to the animal rights group. PETA made the materials they received available to the other stakeholders, most of whom, like PETA, had only opposed SB 1381 prior to its amended and passed form, and who had no idea that the VDACS had been soliciting comment with regards to drafting the guidance paper.

"I was surprised to hear that there is an interpretation of the bill which gives impetus to writing new regulations that affect private shelters, if that is indeed the case. The purpose of moving the language 'operated for the purpose of finding permanent adoptive homes for animals' from a lower line to the first line of that section of Code was presented to the Agriculture Committee as a statement of emphasis to insure that all shelters make an attempt to adopt out animals. 'Private shelters operating on charitable dollars should make a sincere effort to get animals adopted rather than kill them,' as one proponent stated. There was no discussion of regulation changes or any other requirements intended with passage of the bill."--Delegate Danny Marshal, in a Letter to VDACS About the Drafting of the Guidance Document

When looking through the materials pertaining to both the process of passing SB 1381 and the private drafting of the VDACS' guidance document, it's clear that many of the participants were aware that the private group was endeavoring to enact regulations contrary to the statute in its content. On January 29, 2015, during testimony she gave in front of the Senate Agriculture, Conservation and Natural Resources Committee, Debra Griggs, the president of the Virginia Federation of Humane Societies and founder of No Kill Hampton Roads, stated the following:

"My name is Debra Griggs and I am the president of the Virginia Federation of Humane Societies. We believe this bill closes the loophole in the definition of private animal shelter to make it abundantly clear that finding permanent adoptive homes is a purpose of those shelters. This does not affect public shelters only private shelters. It doesn't say private animal shelters must succeed at finding permanent adoptive homes just that it must be one of your purposes."

In a February 25, 2015, blog post for the Richmond SPCA, Robin Starr writes:

"It was a modest bill that simply made clear that private shelters operating on charitable dollars should make a sincere effort to get animals adopted rather than just killing them all. It was not, as the hysterics have claimed, an effort to force all private shelters in Virginia to be no kill or to prevent them from being able to euthanize animals. That was an irresponsible claim all along since the right of shelters to euthanize is set forth in a separate code section that has not changed at all."

And the VDACS has certainly already been through this; back in 2010 when the State Veterinarian conducted that "site visit" to PETA's shelter, operating under the false impression that the statutory definition of "animal shelter" established that private shelters must operate for a primary purpose of finding animals permanent adoptive homes. The VDACS now maintains that they believed that the guidance document was necessary because the restructuring of SB 1381 established that private animal shelters must operate for the primary purpose of finding permanent adoptive homes, even though the word "primary" appears nowhere in the statute. A confusing claim since the statute itself doesn't provide that the placement of the phrase "operated for the purpose of finding permanent adoptive homes for animals" has any bearing on other shelter operations. In addition to the stakeholders who initially opposed SB 1381, the Delegates who actually passed the legislation feel that the VDACS is overreaching its regulation of private animal shelters by interpreting the statute that way:

"I have been made aware that the Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services has overreached its regulation of private shelters above and beyond the intent of SB 1381. … If the intent of SB 1381 needs to be polished then we have the entire year to speak about those changes and have recommendations for the 2016 legislative session."--Delegate Barry Knight, in a Letter to VDACS About the Guidance Document

"VDACS plans to develop a new regulation through the Administrative Process Act to further clarify the qualifications for a facility 'operated for the purpose of finding permanent adoptive homes for animals.' The agency expects that the three-step regulatory process required by the Code of Virginia will take two to three years to complete given the extensive stakeholder interest in this issue. The impact of the law on PETA or any other private animal shelter will not be known until the regulation is finalized."--VDACS' Statement to Huffington Post

Though Delegates that passed the amended legislation would later state that the bill never established that private animal shelters must operate for any primary purpose, and though the bill had never even contained the word "primary" or any of its synonyms, forces within Virginia and beyond redoubled their efforts to establish a "primary purpose" requirement with regards to private animal shelters, outside of the statute, by way of an accompanying "guidance document." On April 16, 2015, at their request, the VDACS met with what was described as "a number of proponents of SB 1381" to get their input; SB 1381 patron Senator William Stanley Jr., Debra Griggs of the Virginia Federation of Humane Societies, Robin Starr of the Richmond SPCA, and Will Gomaa of Maryland-based Alley Cat Allies met with VDACS Deputy Secretary of Agriculture Sam Towell, VDACS Commissioner Sandy Adams, and State Veterinarian Dr. Richard Wilkes, to express their concerns. The group of supporters was asked to submit their suggestions for a "guidance document" the VDACS would be drafting.

The VDACS rarely creates guidance documents. In fact, this guidance document was the first ever of its kind. But what made this particular document even more noteworthy was that the VDACS and several of the legislation's supporters were working together privately to draft it. Over the span of many weeks, the VDACS was creating regulations that would be put in place as soon as July 1, 2015, and they were doing it out of the view of most of the document's stakeholders. And what was maybe even more concerning was that the group seemed to be endeavoring to enact regulations contrary to the statute in its content. On April 28, 2015, barely a month after SB 1381 was signed into law, and two weeks after the VDACS had met privately with the group of SB 1381 supporters, VDACS officials were already going forth with the premise that the statute itself established that private animal shelters must operate for the primary purpose of providing permanent adoptive homes for animals, though Delegates who passed the bill would later say it didn't:

"SB 1381 changed the definition of a public animal shelter to require that a shelter have the finding of permanent, adoptive homes for companion animals as the primary mission of the facility. VDACS is developing criteria that will determine the primary mission of a public shelter and hopes to start using the definition for inspections near July 1. A facility must be designated as a shelter to be allowed to have trained and approved non-veterinarians perform euthanasia."--Dr. Wilkes, Virginia State Veterinarian in a Letter to the Virginia Veterinary Medical Association Dated April 28, 2015

It wasn't until May 6, 2015, and quite by accident, that word leaked out that SB 1381 supporters were meeting privately with VDACS officials to create the guidance document, and that regulation was on track to be implemented way ahead of the two to three year time frame the VDACS had committed to back in March. On May 7, 2015, PETA submitted a Freedom of Information Act request to the VDACS to obtain the materials pertaining to the drafting of the guidance document, at considerable expense to the animal rights group. PETA made the materials they received available to the other stakeholders, most of whom, like PETA, had only opposed SB 1381 prior to its amended and passed form, and who had no idea that the VDACS had been soliciting comment with regards to drafting the guidance paper.

"I was surprised to hear that there is an interpretation of the bill which gives impetus to writing new regulations that affect private shelters, if that is indeed the case. The purpose of moving the language 'operated for the purpose of finding permanent adoptive homes for animals' from a lower line to the first line of that section of Code was presented to the Agriculture Committee as a statement of emphasis to insure that all shelters make an attempt to adopt out animals. 'Private shelters operating on charitable dollars should make a sincere effort to get animals adopted rather than kill them,' as one proponent stated. There was no discussion of regulation changes or any other requirements intended with passage of the bill."--Delegate Danny Marshal, in a Letter to VDACS About the Drafting of the Guidance Document

When looking through the materials pertaining to both the process of passing SB 1381 and the private drafting of the VDACS' guidance document, it's clear that many of the participants were aware that the private group was endeavoring to enact regulations contrary to the statute in its content. On January 29, 2015, during testimony she gave in front of the Senate Agriculture, Conservation and Natural Resources Committee, Debra Griggs, the president of the Virginia Federation of Humane Societies and founder of No Kill Hampton Roads, stated the following:

"My name is Debra Griggs and I am the president of the Virginia Federation of Humane Societies. We believe this bill closes the loophole in the definition of private animal shelter to make it abundantly clear that finding permanent adoptive homes is a purpose of those shelters. This does not affect public shelters only private shelters. It doesn't say private animal shelters must succeed at finding permanent adoptive homes just that it must be one of your purposes."

In a February 25, 2015, blog post for the Richmond SPCA, Robin Starr writes:

"It was a modest bill that simply made clear that private shelters operating on charitable dollars should make a sincere effort to get animals adopted rather than just killing them all. It was not, as the hysterics have claimed, an effort to force all private shelters in Virginia to be no kill or to prevent them from being able to euthanize animals. That was an irresponsible claim all along since the right of shelters to euthanize is set forth in a separate code section that has not changed at all."

And the VDACS has certainly already been through this; back in 2010 when the State Veterinarian conducted that "site visit" to PETA's shelter, operating under the false impression that the statutory definition of "animal shelter" established that private shelters must operate for a primary purpose of finding animals permanent adoptive homes. The VDACS now maintains that they believed that the guidance document was necessary because the restructuring of SB 1381 established that private animal shelters must operate for the primary purpose of finding permanent adoptive homes, even though the word "primary" appears nowhere in the statute. A confusing claim since the statute itself doesn't provide that the placement of the phrase "operated for the purpose of finding permanent adoptive homes for animals" has any bearing on other shelter operations. In addition to the stakeholders who initially opposed SB 1381, the Delegates who actually passed the legislation feel that the VDACS is overreaching its regulation of private animal shelters by interpreting the statute that way:

"I have been made aware that the Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services has overreached its regulation of private shelters above and beyond the intent of SB 1381. … If the intent of SB 1381 needs to be polished then we have the entire year to speak about those changes and have recommendations for the 2016 legislative session."--Delegate Barry Knight, in a Letter to VDACS About the Guidance Document

Delegate Bobby Orrock Introduces Legislation to Preserve Private Shelters' Abilities to Serve Animals on a Case by Case Basis

On December 22, 2015 and January 5, 2016, respectively, Delegate Bobby Orrock introduced HB156 and HB340, legislation seeking to clarify the definition of "private animal shelter" and affirm private animals shelters' lawful purposes, and HB157, legislation seeking to reaffirm the requirement of public transparency with regards to the potential development of a "guidance document" that may someday accompany legislation pertaining to private animal shelters. On January 20, 2016, Delegate Orrock introduced HB1270, a mandate that will direct the State Veterinarian to "establish a seven-member advisory committee to make recommendations and serve as a resource in the development of policies related to the care and treatment of companion animals by public and private animal shelters." HB340 passed both House and Senate vote, with amendments, HB157 has been sidelined until 2017, pending the outcome of HB1270, which is still viable and likely to be passed.

Learn more here:

Learn more here:

Despite What Its Proponents Tell You, SB 1381 Doesn't Impact Euthanasia in Private Animal Shelters

Below is the section of Virginia code that provides for the euthanasia of shelter animals, emphasis has been added to the sections directly pertaining to the circumstances under which shelter animals may be euthanized. Preceding the code are definitions pertinent to understanding the material.

"Humane society" means any incorporated, nonprofit organization that is organized for the purposes of preventing cruelty to animals and promoting humane care and treatment or adoptions of animals.

"Facility" means a building or portion thereof as designated by the State Veterinarian, other than a private residential dwelling and its surrounding grounds, that is used to contain a primary enclosure or enclosures in which animals are housed or kept.

"Private animal shelter" means a facility operated for the purpose of finding permanent adoptive homes for animals that is used to house or contain animals and that is owned or operated by an incorporated, nonprofit, and nongovernmental entity, including a humane society, animal welfare organization, society for the prevention of cruelty to animals, or any other similar organization.

"Releasing agency" means (i) a public animal shelter or (ii) a private animal shelter, humane society, animal welfare organization, society for the prevention of cruelty to animals, or other similar entity or home-based rescue that releases companion animals for adoption.

§ 3.2-6548. Private animal shelters; confinement and disposition of animals; affiliation with foster care providers; penalties; injunctive relief.

Bills amending this Section

A. A private animal shelter may confine and dispose of animals in accordance with the provisions of subsections B through G of § 3.2-6546.

A. For purposes of this section:

"Animal" shall not include agricultural animals.

"Rightful owner" means a person with a right of property in the animal.

B. The governing body of each county or city shall maintain or cause to be maintained a public animal shelter and shall require dogs running at large without the tag required by § 3.2-6531 or in violation of an ordinance passed pursuant to § 3.2-6538 to be confined therein. Nothing in this section shall be construed to prohibit confinement of other companion animals in such a shelter. The governing body of any county or city need not own the facility required by this section but may contract for its establishment with a private group or in conjunction with one or more other local governing bodies. The governing body shall require that:

C. An animal confined pursuant to this section shall be kept for a period of not less than five days, such period to commence on the day immediately following the day the animal is initially confined in the facility, unless sooner claimed by the rightful owner thereof.

The operator or custodian of the public animal shelter shall make a reasonable effort to ascertain whether the animal has a collar, tag, license, tattoo, or other form of identification. If such identification is found on the animal, the animal shall be held for an additional five days, unless sooner claimed by the rightful owner. If the rightful owner of the animal can be readily identified, the operator or custodian of the shelter shall make a reasonable effort to notify the owner of the animal's confinement within the next 48 hours following its confinement.

If any animal confined pursuant to this section is claimed by its rightful owner, such owner may be charged with the actual expenses incurred in keeping the animal impounded. In addition to this and any other fees that might be levied, the locality may, after a public hearing, adopt an ordinance to charge the owner of an animal a fee for impoundment and increased fees for subsequent impoundments of the same animal.

D. If an animal confined pursuant to this section has not been claimed upon expiration of the appropriate holding period as provided by subsection C, it shall be deemed abandoned and become the property of the public animal shelter. Such animal may be euthanized in accordance with the methods approved by the State Veterinarian or disposed of by the methods set forth in subdivisions 1 through 5. No shelter shall release more than two animals or a family of animals during any 30-day period to any one person under subdivisions 2, 3, or 4.

For purposes of recordkeeping, release of an animal by a public animal shelter to a public or private animal shelter or other releasing agency shall be considered a transfer and not an adoption. If the animal is not first sterilized, the responsibility for sterilizing the animal transfers to the receiving entity.

Any proceeds deriving from the gift, sale, or delivery of such animals shall be paid directly to the treasurer of the locality. Any proceeds deriving from the gift, sale, or delivery of such animals by a public or private animal shelter or other releasing agency shall be paid directly to the clerk or treasurer of the animal shelter or other releasing agency for the expenses of the society and expenses incident to any agreement concerning the disposing of such animal. No part of the proceeds shall accrue to any individual except for the aforementioned purposes.

E. Nothing in this section shall prohibit the immediate euthanasia of a critically injured, critically ill, or unweaned animal for humane purposes. Any animal euthanized pursuant to the provisions of this chapter shall be euthanized by one of the methods prescribed or approved by the State Veterinarian.

F. Nothing in this section shall prohibit the immediate euthanasia or disposal by the methods listed in subdivisions 1 through 5 of subsection D of an animal that has been released to a public or private animal shelter, other releasing agency, or animal control officer by the animal's rightful owner after the rightful owner has read and signed a statement: (i) surrendering all property rights in such animal; (ii) stating that no other person has a right of property in the animal; and (iii) acknowledging that the animal may be immediately euthanized or disposed of in accordance with subdivisions 1 through 5 of subsection D.

G. Nothing in this section shall prohibit any feral dog or feral cat not bearing a collar, tag, tattoo, or other form of identification that, based on the written statement of a disinterested person, exhibits behavior that poses a risk of physical injury to any person confining the animal, from being euthanized after being kept for a period of not less than three days, at least one of which shall be a full business day, such period to commence on the day the animal is initially confined in the facility, unless sooner claimed by the rightful owner. The statement of the disinterested person shall be kept with the animal as required by § 3.2-6557. For purposes of this subsection, a disinterested person shall not include a person releasing or reporting the animal.

Bills amending this Section

A. A private animal shelter may confine and dispose of animals in accordance with the provisions of subsections B through G of § 3.2-6546.

A. For purposes of this section:

"Animal" shall not include agricultural animals.

"Rightful owner" means a person with a right of property in the animal.

B. The governing body of each county or city shall maintain or cause to be maintained a public animal shelter and shall require dogs running at large without the tag required by § 3.2-6531 or in violation of an ordinance passed pursuant to § 3.2-6538 to be confined therein. Nothing in this section shall be construed to prohibit confinement of other companion animals in such a shelter. The governing body of any county or city need not own the facility required by this section but may contract for its establishment with a private group or in conjunction with one or more other local governing bodies. The governing body shall require that:

- The public animal shelter shall be accessible to the public at reasonable hours during the week;

- The public animal shelter shall obtain a signed statement from each of its directors, operators, staff, or animal caregivers specifying that each individual has never been convicted of animal cruelty, neglect, or abandonment, and each shelter shall update such statement as changes occur;

- If a person contacts the public animal shelter inquiring about a lost companion animal, the shelter shall advise the person if the companion animal is confined at the shelter or if a companion animal of similar description is confined at the shelter;

- The public animal shelter shall maintain a written record of the information on each companion animal submitted to the shelter by a private animal shelter in accordance with subsection D of § 3.2-6548 for a period of 30 days from the date the information is received by the shelter. If a person contacts the shelter inquiring about a lost companion animal, the shelter shall check its records and make available to such person any information submitted by a private animal shelter or allow such person inquiring about a lost animal to view the written records;

- The public animal shelter shall maintain a written record of the information on each companion animal submitted to the shelter by a releasing agency other than a public or private animal shelter in accordance with subdivision F 2 of § 3.2-6549 for a period of 30 days from the date the information is received by the shelter. If a person contacts the shelter inquiring about a lost companion animal, the shelter shall check its records and make available to such person any information submitted by such releasing agency or allow such person inquiring about a lost companion animal to view the written records; and

- The public animal shelter shall maintain a written record of the information on each companion animal submitted to the shelter by an individual in accordance with subdivision A 2 of § 3.2-6551 for a period of 30 days from the date the information is received by the shelter. If a person contacts the shelter inquiring about a lost companion animal, the shelter shall check its records and make available to such person any information submitted by the individual or allow such person inquiring about a lost companion animal to view the written records.

C. An animal confined pursuant to this section shall be kept for a period of not less than five days, such period to commence on the day immediately following the day the animal is initially confined in the facility, unless sooner claimed by the rightful owner thereof.

The operator or custodian of the public animal shelter shall make a reasonable effort to ascertain whether the animal has a collar, tag, license, tattoo, or other form of identification. If such identification is found on the animal, the animal shall be held for an additional five days, unless sooner claimed by the rightful owner. If the rightful owner of the animal can be readily identified, the operator or custodian of the shelter shall make a reasonable effort to notify the owner of the animal's confinement within the next 48 hours following its confinement.

If any animal confined pursuant to this section is claimed by its rightful owner, such owner may be charged with the actual expenses incurred in keeping the animal impounded. In addition to this and any other fees that might be levied, the locality may, after a public hearing, adopt an ordinance to charge the owner of an animal a fee for impoundment and increased fees for subsequent impoundments of the same animal.

D. If an animal confined pursuant to this section has not been claimed upon expiration of the appropriate holding period as provided by subsection C, it shall be deemed abandoned and become the property of the public animal shelter. Such animal may be euthanized in accordance with the methods approved by the State Veterinarian or disposed of by the methods set forth in subdivisions 1 through 5. No shelter shall release more than two animals or a family of animals during any 30-day period to any one person under subdivisions 2, 3, or 4.

- Release to any humane society, public or private animal shelter, or other releasing agency within the Commonwealth, provided that each humane society, animal shelter, or other releasing agency obtains a signed statement from each of its directors, operators, staff, or animal caregivers specifying that each individual has never been convicted of animal cruelty, neglect, or abandonment and updates such statements as changes occur;

- Adoption by a resident of the county or city where the shelter is operated and who will pay the required license fee, if any, on such animal, provided that such resident has read and signed a statement specifying that he has never been convicted of animal cruelty, neglect, or abandonment;

- Adoption by a resident of an adjacent political subdivision of the Commonwealth, if the resident has read and signed a statement specifying that he has never been convicted of animal cruelty, neglect, or abandonment;

- Adoption by any other person, provided that such person has read and signed a statement specifying that he has never been convicted of animal cruelty, neglect, or abandonment and provided that no dog or cat may be adopted by any person who is not a resident of the county or city where the shelter is operated, or of an adjacent political subdivision, unless the dog or cat is first sterilized, and the shelter may require that the sterilization be done at the expense of the person adopting the dog or cat; or

- Release for the purposes of adoption or euthanasia only, to an animal shelter, or any other releasing agency located in and lawfully operating under the laws of another state, provided that such animal shelter, or other releasing agency: (i) maintains records that would comply with § 3.2-6557; (ii) requires that adopted dogs and cats be sterilized; (iii) obtains a signed statement from each of its directors, operators, staff, and animal caregivers specifying that each individual has never been convicted of animal cruelty, neglect, or abandonment, and updates such statement as changes occur; and (iv) has provided to the public or private animal shelter or other releasing agency within the Commonwealth a statement signed by an authorized representative specifying the entity's compliance with clauses (i) through (iii), and the provisions of adequate care and performance of humane euthanasia, as necessary in accordance with the provisions of this chapter.

For purposes of recordkeeping, release of an animal by a public animal shelter to a public or private animal shelter or other releasing agency shall be considered a transfer and not an adoption. If the animal is not first sterilized, the responsibility for sterilizing the animal transfers to the receiving entity.

Any proceeds deriving from the gift, sale, or delivery of such animals shall be paid directly to the treasurer of the locality. Any proceeds deriving from the gift, sale, or delivery of such animals by a public or private animal shelter or other releasing agency shall be paid directly to the clerk or treasurer of the animal shelter or other releasing agency for the expenses of the society and expenses incident to any agreement concerning the disposing of such animal. No part of the proceeds shall accrue to any individual except for the aforementioned purposes.

E. Nothing in this section shall prohibit the immediate euthanasia of a critically injured, critically ill, or unweaned animal for humane purposes. Any animal euthanized pursuant to the provisions of this chapter shall be euthanized by one of the methods prescribed or approved by the State Veterinarian.

F. Nothing in this section shall prohibit the immediate euthanasia or disposal by the methods listed in subdivisions 1 through 5 of subsection D of an animal that has been released to a public or private animal shelter, other releasing agency, or animal control officer by the animal's rightful owner after the rightful owner has read and signed a statement: (i) surrendering all property rights in such animal; (ii) stating that no other person has a right of property in the animal; and (iii) acknowledging that the animal may be immediately euthanized or disposed of in accordance with subdivisions 1 through 5 of subsection D.

G. Nothing in this section shall prohibit any feral dog or feral cat not bearing a collar, tag, tattoo, or other form of identification that, based on the written statement of a disinterested person, exhibits behavior that poses a risk of physical injury to any person confining the animal, from being euthanized after being kept for a period of not less than three days, at least one of which shall be a full business day, such period to commence on the day the animal is initially confined in the facility, unless sooner claimed by the rightful owner. The statement of the disinterested person shall be kept with the animal as required by § 3.2-6557. For purposes of this subsection, a disinterested person shall not include a person releasing or reporting the animal.

The Association of Shelter Veterinarians' Recommendations Regarding Euthanasia

|

"The Association of Shelter Veterinarians supports the development of animal shelter operational policies based on an organization’s capacity for humane care and available resources, regardless of organizational philosophy. The guiding principle in the provision of humane care should always be animals’ needs, which remain the same regardless of an organization’s mission or challenges in meeting those needs. Many shelters employ 'no-kill' or 'adoption-guarantee' terminology to describe humane work.

"This terminology lacks a clear and consistent definition which may result in confusion, misperception, or discord within communities. Definitions of 'no-kill' vary along a spectrum and may include policies that prevent euthanasia of animals for lack of housing, those that prevent euthanasia of behaviorally or medically healthy animals, those that prevent euthanasia of animals with conditions considered treatable by reasonable pet owners in their community, or those that prohibit euthanasia of animals at all costs. As such, the ASV discourages the use of terminology that defines an organization based on euthanasia practices. "Euthanasia of companion animals is a tool to prevent animal suffering. In any sheltering facility, including those that identify as 'no-kill', humane euthanasia may be necessary to control suffering in animals with untreatable medical or behavioral conditions or in the interest of public safety. Additionally, euthanasia of healthy and treatable companion animals is sometimes utilized in order to maintain a shelter’s capacity for humane care. When an organization’s capacity for care is exceeded, animal suffering ensues." |